Some wit coined the term “Guerrilla Filmmaking”, derived from the Spanish word for “little war”. It refers to filmmaking by whatever means necessary.

It suggests a people’s rebellion; shock tactics in public places, unpredictable outcomes and secret manœuvres, life and death. I liked the idea of “skeleton” crews armed with lights and a camera, grabbing opportunities without permission, viewing our common world through uncommon eyes.

It’s all voodoo and very glamorous.

The head of the film school Brian Robinson and the lecturers John Bird and Nigel Buesst set exercises for students, and a lot of writing took place in the first semester in order to develop a final script for production, beginning mid year.

Brian’s exercises required students to explore ideas like image, sound and movement, resulting in simple half-page scenes. The fourth exercise became the basis for my first draft script. It was called "Little Doin’s In The Dunes” and included the first clear description of an incident that was used in the final script.

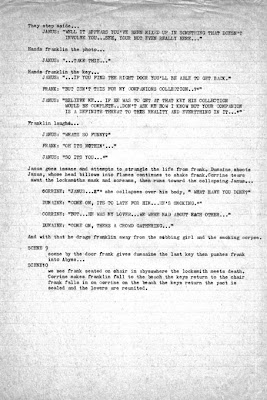

THE HANDWRITTEN PAGES OF "LITTLE DOIN'S IN THE DUNES" AS THEY WERE ASSESSED BY BRIAN ROBINSON

My experience of film was mainstream compared to the diploma students, who had a broader knowledge of movie culture. We watched a lot of stuff and I got filled in fast.

I was interested in making a short that referenced “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” (Luis Buñuel, 1972), “The Third Man” (Carol Reed, 1949) and especially “Alphaville” (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965).

I’d seen “Eraserhead” earlier that year, and the anxiety that film provoked had a major impact on me. These movies shared the sense of a dream, with the danger and wonder of worlds displaced by a surreal mysticism. I wanted to emulate these enigmatic and anarchic films, and all we had to do was point and shoot.

I wrote a summary of intention about the second semester final film project. This summary was to be used in discussion, for more writing and editing. I presented it to lecturer John Bird, and as required I read it out aloud to other students in the course to gauge the interest of potential collaborators.

During my reading a number of my peers walked out led by Bruce Kerr, a professional actor who trod the boards. He aimed to bring his skills to directing. Bon voyage buddy.

John Bird’s response to my proposal was: “An ambitious little piece…”, which it was.

JOHN BIRD'S ASSESSMENT OF MY PROPOSAL

I was most rankled by his comment, “I suspect you will not believe our judgements on the complexities entailed until you have attempted them yourself. I think you have neither the expertise available or the experience, yet, to realise this on film…”.

How right he was, and how like a red rag to a bull in a china shop.

I promptly asked my friends to help shoot a test scene. I bulldozed my first script summary and kept writing stuff connected to “Little Doin’s In The Dunes”.

In the process, I ripped off a few images and dialogue from the work of French cartoonist Moebius, mostly from “The Airtight Garage of Jerry Cornelius”, itself derived from Michael Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius saga. I accidently embraced the ideals of collage, homage and acquisition without knowing how post-modern I was.

I was self-righteous, hungover and pressed for time, so I plagiarised.

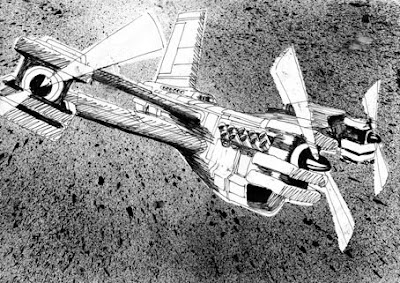

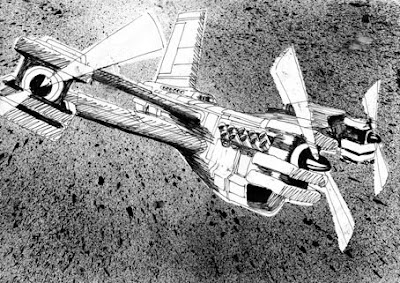

In fact if you compare some of Moebius' drawings from that comic with my storyboards, you'll see I "referenced" him for a few frames during the Janus assassination scene.

The “sampled” images and scraps of dialogue from Moebius inspired turning points in my plot, most memorably when Janus gets shot, his head bursts into flame and as he smoulders the heroine pleads, “But we were lovers, we were mad about each other.” To which the hero responds, “Come on, it’s too late for him. He’s smoking.”

So was I, and Mary Jane danced laterally with Peter Stuyvesant, the passport to smoking pleasure and substance abuse.

I elaborated on this material, wrote a new treatment and did some storyboards, making it into a supernatural conspiracy that brings separated lovers together.

LARGE STYLE FRAMES - PENCIL, BRUSH, INK AND WHITE OUT

I completed a very large pencil and ink drawing of the cockpit of the seaplane, which I've enlarged to give a sense of the detail.

I cast my friends Tim Skerritt and Frank Trobbiani as the lead protagonists and out of the blue Paul Goldman volunteered to be the Director of Photography and Camera Operator. He had spent some time at Swinburne becoming a talented cinematographer, and much of the film's impact is due to his grasp of the technical requirements of filmmaking and his complete understanding of what I hoped to achieve in ten minutes.

Along with his girlfriend and camera assistant Lucy MacLaren and a few other volunteers, we shot the first major scene with Tim and Frank on a rainy night, using high and low angles, great "film noir" lighting and a smoke machine. The camera was severely flooded, redheads exploded and we all got drenched, but the scene worked and within a week I got the nod from Brian.

STILL FRAMES FROM THE TEST SCENE AS USED IN THE FINAL FILM, WITH FRANK TROBBIANI AND TIM SKERRITT PLAYING FRANKLIN AND DUMAINE

It was physical filmmaking, emphasis on the word making – no digital equipment. Working a light meter, adjusting lenses, walking backwards while shooting, recording sound with a boom.

It was all highly mobile and had great jargon. Magazines were loaded with stock inside a black bag like a magic act. Wheelchairs worked for dolly shots, tripods were big and heavy and tape recorders reel-to-reel. Exposed footage was processed overnight as the next day’s rushes, and sound was manually transferred from recording to cutting tape.

My only bloody skirmish was with a sound transfer machine. When the tape finished the weighted spools kept spinning. I tried to stop them and the spools bit me, tearing the knuckles off both hands.

Shaken, I walked out like a surgeon waiting for gloves, blood pouring down my wrists and arms. The women at reception patched me up and I never went near the thing again.

I found a postcard of a very old William Blake etching, an image of a man about to climb a ladder to the moon, titled “I want. I want.”

It filled me with hope and fear.

I went out at night and found locations where we could conjure dreamscapes.

In dreams we cross mysterious borderlands, down a maze of broken cobblestone laneways, gothic stone haunts invaded by sinuous nature. Collecting lost buttons we can never take home, climbing ladders into hideaways where well-known strangers and unrecognisable friends pick at their elbows, watching apocalyptic moons rise with big owl eyes.

After six rough drafts I typed up the final script, mangling it into a supernatural conspiracy.